Download · Introduction · Events · Interview · Abstracts · Contents · Contributors · Funding

Jetzt auf Deutsch (Open Access Download):

Die Kill Cloud · Auswirkungen der netzwerzentrierten Kriegsführung auf die reale Welt

Lisa Ling & Cian Westmoreland

Introduction · Back to top

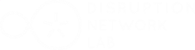

Whistleblowing for Change

Exposing Systems of Power & Injustice

TATIANA BAZZICHELLI (ED.)

ORDER PRINT VERSION (29,50€)

from Transcript Verlag, November 2021.

Other shops: Dussmann (DE), Columbia University Press (US), WHSmith (UK)

FREE DIGITAL VERSIONS:

Download EPUB / PDF

The courageous acts of whistleblowing that inspired the world over the past few years have changed our perception of surveillance and control in today's information society. But what are the wider effects of whistleblowing as an act of dissent on politics, society, and the arts? How does it contribute to new courses of action, digital tools, and contents? This urgent intervention based on the work of Berlin's Disruption Network Lab examines this growing phenomenon, offering interdisciplinary pathways to empower the public by investigating whistleblowing as a developing political practice that has the ability to provoke change from within.

Events · Back to top

Events

Watch our book launch conference

with Reality Winner, John Kiriakou, Daryl Davis, Barrett Brown & more!

Click to load YouTube-video

Interview with Tatiana Bazzichelli · Back to top

A timely guide to exposing systems of power. Tatiana Bazzichelli shows how whistleblowing contributes to shaping change in our digitised world.

-

Whistleblowing is one of the most difficult means of exposing misconducts and informing the public about unknown facts that must be revealed. It is an act based on ethics, honesty and accountability, that confronts abuses, discrimination, corruption and exploitation. Whistleblowers are people that want to change systems for the better, but that in many cases encounter reprisal and persecution. Often, they trust the systems too much, realising at high personal costs that these systems are not willing to improve. This introduction addresses the importance of whistleblowing to generate public awareness and critical thinking towards power structures. Drawing upon her background in the field of activism, network culture and art, Tatiana Bazzichelli follows a speculative approach, connecting whistleblowing with cultural, artistic, and political interventions. Referring to the notion of disruption as a conscious tactic of interfering with surveillance systems and pervasive forms of control, whistleblowing is seen through its potential for social transformation. An open debate around whistleblowing becomes an opportunity to envision new tactics of criticism in the information society.

-

Billie Jean Winner-Davis, mother of US National Security whisteblower Reality Leigh Winner, provides a narrative of her journey alongside her daughter, after her daughter’s arrest and persecution by the United States Department of Justice under Trump. Billie’s daughter Reality Winner is an ex-NSA contractor who held a high security clearance following her discharge from the Air Force. At a time when Trump was attempting to stop the investigation into Russian election interference in the US 2016 presidential elections, Reality Winner took it upon herself to anonymously release a document containing details of the Russian spear phishing attempts to gain access to voting software and information. Reality Winner was promptly arrested and charged under the Espionage Act, denied bail, and forced to accept a plea deal that would land her in prison for close to 4 years. This chapter was written by Billie Winner-Davis, in order to provide a parent’s view about what was done to her child and how the uneven playing field prompted her to advocate for her daughter in any way that she could.

-

What happens when a CIA counterterrorism officer is asked to violate the human rights of a prisoner? What happens when that CIA officer, in a crisis of conscience, decides to go public with what he believes are his agency’s crimes against humanity? This is the story of John Kiriakou and his capture of Abu Zubaydah, thought to be al-Qaeda’s #3, who was subjected to unspeakable torture at the hands of Kiriakou’s colleagues. Kiriakou is considered the first US intelligence officer to reveal information about the US intelligence community’s use of torture techniques. A former CIA officer, he became a whistleblower when he told ABC News in December 2007 that the CIA was torturing al-Qaeda prisoners. Immediately after his interview, the Justice Department initiated a years-long investigation, determined to find something to charge him with. John was eventually charged with three counts of espionage, one count of violating the Intelligence Identities Protection Act and one count of making a false statement as a result of the ABC News interview. In February 2013, after pleading guilty to violating the Intelligence Identities Protection Act, Kiriakou began serving his prison sentence.

-

Brandon Bryant, MQ-1B Predator sensor operator who joined the US Air Force from 2005 to 2011, writes about his personal experience as a US veteran. Brandon Bryant was among the first drone operators to speak out publicly about conditions of the unmanned aerial vehicles’ programme of which he was a member from 2006 to 2011, particularly the US Air Force Predator programme, which was responsible for several drone strikes and attacks overseas. In describing a personal war experience, he deals with questions of power, technology, and ethics, and how they shape our personal life when we enter directly into contact with warfare using remotely controlled technologies. Both invisible and remote, these military systems create a surreal temporary zone in which the operator works; a zone where life and death intertwine. This chapter reflects on the importance of generating public awareness and critical thinking towards power structures, and most of all, the act of changing perspective and readdressing and revising the artificial dichotomy of whistleblowers as being either heroes or traitors.

-

Way back in the late 1990s, Annie Machon was working as an intelligence officer for the UK domestic Security Service, MI5, when with her former partner and colleague, David Shayler, they decided to blow the whistle, thereby facing arrest and prosecution for daring to speak out about deep state crimes. Since that experience, she began strongly criticising those legal and political machinations behind the scenes and the media manipulation rising from incompetence and crime inside the UK domestic security service, in the name of the vital need for personal privacy and picturing the vested interests that roll on untouched. Her contribution brings to the table the case of Edward Snowden and an introduction to the WikiLeaks system in order to trigger awareness of the importance of having the ability to speak safely. The result is a valuable analysis on important cases of whistleblowing which emphasises their need to be protected and valued, instead of persecuted and prosecuted.

-

The 2013 debate on the PRISM, XKeyscore, and TEMPORA internet surveillance programmes, based on the NSA documents Edward Snowden disclosed to journalists, symbolised an increasing geopolitical control. New identities emerged: whistleblowers, cyberpunks, hacktivists and individuals that brought attention to abuses of government and large corporations, making the act of leaking a central part of their strategy.

This section deals with the effects of this debate on art and culture, presenting the concept of Art as Evidence, a notion suggested by Laura Poitras in 2013. Tatiana Bazzichelli engages with the artistic potential of revealing facts, exposing misconduct and wrongdoings, and promoting awareness about social, political, and technological matters. Bazzichelli’s analysis traces the background of the concept of Art as Evidence, and the effects of whistleblowing on art and culture, covering the time frame from the early WikiLeaks projects to the impact of the Snowden disclosures. Art as Evidence encourages the creation of art through critical models of thinking and understanding, as well as stresses the role of artistic creation to investigate issues and translate information.

-

Academy Award-winning filmmaker and journalist Laura Poitras reflects on the role of art as evidence. In her movies and documentaries on topics such as the US occupation of Iraq, the war on terror and Guantanamo Bay Prison, NSA surveillance, Edward Snowden and Julian Assange cases, she uses multiple disciplines and methodologies to understand ground truths and to present them in a variety of contexts, addressing the production of evidence as a collaborative act by civil society. In two interviews with Tatiana Bazzichelli in 2014 and 2021, Poitras explains how she pushed the publication of critical stories to denounce what she defines a tragic lack of freedom of the press and the evident effort of the government’s sneaks to silence and criminalise critical people. Reflecting on the silence of the press around the persecution of Julian Assange, as well as The Intercept’s failure to protect Reality Winner and the lack of accountability that followed, she argues that we must guarantee an adequate protection for whistleblowers if they reach the press, and how it should be made possible that what they reveal has an impact on society.

-

The artist and geographer Trevor Paglen reflects on his artistic practice and on the connections with whistleblowing. Interviewed by Tatiana Bazzichelli, Trevor Paglen contextualises the implications for surveillance and privacy in all public and private environments within the factual possibility of modern surveillance states. While big systems of control such as the CIA, FBI and NSA were raised to answer the big fears of society such as terrorism and climate change, the real terror became the considerable size of power that the State took instead, with a consequence on state’s civic capacities and justified control on citizens. In such context, Paglen describes how he uses his art to divulge evidence to propel people’s cultural reflection and their ability to see the world around them. Its photography of hidden military bases, secret air sites, undersea network cables, and offshore prisons, as well as his works on AI tracking and surveillance and people classification by machines, bring into visibility aspects of society that are hidden, helping us to articulate them.

-

In the 21st century, “big data” whistleblowing and open-source investigation have proposed two different but complementary means of challenging state hegemonies of information. One begins with an overwhelming mass of data; the other with fragmentary image or video evidence. But both attempt to drive change, and pursue accountability for states or militaries, by making data more accessible and comprehensible, and by (re-) connecting that data with real lives, and lived experience. And in that attempt, both practices must navigate the shifting dynamics of the contemporary “public square”, an information-sharing space that could seem hopelessly corrupted by “post-truth”. The work of Forensic Architecture and our partners proposes a path through that space.

-

This chapter introduces what Lisa Ling and Cian Westmoreland have come to call the “Kill Cloud,” a rapidly growing networked infrastructure of global reach with the primary intent of dominating every spectrum of warfare. There is a need for a critical analysis of how the “Kill Cloud” operates, from its ideological underpinnings, its ambitions, to the technological approach being pursued to achieve global military dominance over all battlespace dimensions including, space, cyberspace, and the electromagnetic spectrum itself. Modern network centric warfare has been hidden behind the captivating image of the drone, yet these systems are vastly more complex, insidious, ubiquitous, and inaccurate than the public is aware, and its colonial underpinnings continue to bring endless war to societies across the globe. The Kill Cloud has emerged as an immense and evolving system of systems hastening the expansion of the Global War on Terror. This paper pays close attention to the US military drone programme’s contribution to the framing and evolution of modern network centric war. This Kill Cloud has far-reaching consequences beyond those of what have been traditionally considered in warfare.

-

What if oversight could be a pervasive emergent property of a society? The subject of pervasive invisible surveillance infrastructures informs the reflections of security engineer and activist Lauri Love, who discusses the notion of “Sousveillance'', to denote vigilance upwards from below. He provides an analysis on the current ethical issues concerning technological and intimate surveillance, reflecting on the urge of self-empowering ourselves from centralised power and authority. A romantic recap is given of the history of information dissemination in its role of a check against authority leading to the moment and sublime crisis at hand, and offering just the slightest suggestion of what might be imagined as possible within the work that must be done as the people find that they are a network.

-

In this chapter, Joana Moll explores the role of art and art practice in generating critical awareness on the hidden layers of the so-called data economy apparatus: from its physical infrastructures to the geopolitics of data, corporate surveillance practices, the commodification of user data, and materiality of data. She argues for the importance of exposing critical techno-social arrangements that govern our lives but are mostly opaque to the average citizen, in order to fight the dramatic power asymmetries between the ones designing and running the technical infrastructures and the ones using them. Moreover, she discloses the making of some of her works as an example of how art can be a powerful means to gather evidence and expose wrongdoing. She also argues that gathering evidence is a crucial act to empower users to identify and promote sustainable, transparent, and accountable forms of governance, which are essential to forging a fair and just society.

-

Mostly for the best, sometimes for the worst, hackers have been the heroes of the last decade. Beyond the surface of the tech start-up hype, our heroes had more to do with fighting government corruption, improving journalism, redefining integrity in intelligence and nurturing a modern passion for internationalist social justice. But this came at a high price: first because it created martyrs and second because the hacker image has been tailored around an individualised notion of a super-empowered individual. Interviewed by Tatiana Bazzichelli, Denis “Jaromil” Rojo aims to define ways to re-contextualise hacker ethics in a more collective frame and by provocatively recuperating the ethical lessons that can be learned from corporate and democratic culture beyond its obvious failures.

-

Interviewed by Tatiana Bazzichelli, the two Pulitzer-Prize winning journalists Frederik Obermaier and Bastian Obermayer from Süddeutsche Zeitung explore the impact of the Panama Papers. In 2015, an anonymous whistleblower leaked internal documents from the financial service provider Mossack Fonseca to Obermaier and Obermayer. With the help of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), they launched a worldwide investigation into the secretive world of shell companies. Together with hundreds of colleagues from more than 80 countries they followed the money—the money of prime ministers and the super-rich elite, of organised crime groups, of crooks and of criminals. The exposé led to hundreds of investigations and more than $1.3 billion being recouped by authorities. In their interview, the two investigative journalists discuss the role of whistleblowers, journalists under fire, threats to democracy, and the role of society to fight for a more transparent world.

-

In this chapter, Charlotte Webb uses the metaphor of frost on a spider’s web to present feminist modes of thought and practice as matter that can settle on techno-social webs, revealing their architectures, infrastructures, and power imbalances. She proposes that feminism and whistleblowing share a mindset that wants to expose systems of power, that their energies are aligned in aiming to unveil injustice and rectify it. After presenting a historical look at feminist approaches to technology, she reflects on how feminist practices reveal problematic constructions of gender, race, and class in techno-social systems and the injustices these constructions reproduce. She then discusses the problematic gendering of voice assistants, and introduces a creative project: “Designing a Feminist Alexa”, which brought a community of young people together to develop new imaginaries where voice assistants are conceived differently. She concludes by reflecting on the ways that, while feminist approaches try to make invisible inequalities visible, techno-capitalist logics also demand that the hyper-visibility of women is maintained to uphold the productivity and profitability of platforms.

-

Pelin Ünker presents the story of her reporting on the former Turkish Prime Minister's connections to corporations in Malta, as revealed in the Paradise Papers. She is the only journalist who risked being sent to jail for the Paradise Papers stories. Ünker is an investigative journalist, working for Deutsche Welle as a correspondent in Istanbul. She worked at Cumhuriyet newspaper for ten years as an economics correspondent and finance editor. She has worked on ICIJ’s Panama Papers, Bahamas Leaks, Implant Files, Paradise Papers and FinCEN Files investigations. Her work has included investigations on macroeconomic data on the state of the Turkish economy. She has also investigated corruption, tax avoidance and evasion, privatisations, public contracts, and other subjects.

-

The anonymous collective 15MpaRato was founded in 2012 to condemn scandals and abuses perpetrated by several bankers and politicians with high responsibilities during the 2008-2012 economic crisis in an effort to bring them to the National High Court. Among them, the former minister of economy, Rodrigo Rato, also former vice president and former director of the International Monetary Fund, pleaded guilty together with those involved in the #BlackCards emails scandal and the Bankia Case. In her adaptation of Shreya Tewari and Nani Jansen Reventlow’s interview, Simona Levi digs deeper into the facts, attempting to shine a light on the system of connivance, abuse and impunity on which democracies rest: to show that the government, political-party, big-union and management leaders, all of them have assiduously colluded to extract from the citizenry. So, 15MPARATO is also the story of how, one day, citizens pulled together to change the ending these malfeasants had planned.

-

Christoph Trautvetter explores why ownership structures behind Berlin real estate remain hidden and how exposing them can make a difference to housing policy. Drawing on the information from thousands of tenants and a database of hundreds of Berlin real estate owners, the chapter shows the typical structures used to own real estate—and to stay anonymous. It presents what we know and what we don’t know about ownership structures and debunks the myth of the friendly small-scale owner being the predominant type of owner. The chapter describes how anonymous companies from the British Virgin Islands leading to billionaire heirs, investment funds from Luxembourg and the Cayman Islands, or dirty money from around the world buy up hundreds or even thousands of homes. When tenants start asking who owns their houses, when ownership structures are exposed, and when whistleblowers and good data come together with activists, artists, and politicians, disruptive change is possible.

-

Whistleblowing is seemingly becoming a current trend. From politicians being accused of attempts to illegally sway and even overthrow elections and large corporations being called out for self-serving practices, to the rigging of algorithms on social media platforms such as Facebook, aimed at brainwashing and steering certain users in a particular direction. Overcoming the more traditional definition of whistleblowing, Daryl Davis shines a bright light upon one of his nation's darkest practices, blowing the whistle both on the overt and covert perpetuation of America's ugly practice of racism. The exposé puts under the microscope blatant examples of White supremacy often hidden into subtle code words and fine print, in order to get the reader closer to such modus operandi and to denounce the common lack of protection reserved to this kind of condemners.

-

Magnus Ag invites you in on a personal journey along artists and artistic expressions from the inflatable “Tank Man” in Taipei and Tiananmen Square vigils before they were banned in Hong Kong, to spiritual dance performances in defiance of terror attacks north of Karachi, and to Moscow and creative ways of challenging Putin’s patriarchy. Linked together by a common quest to challenge the dominant narratives, he explores what happens to artistic freedom of expression as media has undergone a fundamental shift from past-directed-recording platforms to a data-driven anticipation of the future, and how digital authoritarianism is exploiting our current digital infrastructure to silence artists and other opposing voices. In face of daunting challenges, he argues that we need the relentless approach of artists around the world and how this must be encouraged and empowered by human rights and other support structures. For whistleblowers and artists to regain the attention needed to create change we need artists to help us reimagine and build alternative digital infrastructure that replace the current market-oriented or authoritarian default approaches and instead put people at the centre.

-

Os Keyes examines the cultural form of the whistleblower, and its prominence within narratives of change. Pointing to not only its raced and gendered associations, but its unspoken dependency on an idealised, individualised form of “resistance”, Keyes argues that whistleblowing as a practice needs to be understood as undertaken as part of broader efforts to achieve change, rather than valorised in isolation. Absent attention to these broader efforts, and the myriad actors involved, idealising the whistleblower at best obscures (and at worst undermines) the achievement of justice.

-

Daniel Hale delivered this 17-minute statement to a courtroom packed with friends, advocates, and other whistleblowers on July 27, 2021 on the date of his sentencing in Alexandria, Virginia. Because of the nature of the Espionage Act, under which Daniel was convicted, he was unable to explain the motives for his disclosures in his own voice prior to this moment. Daniel hand-wrote this statement while incarcerated before his sentencing at the Alexandria Adult Detention Center.

-

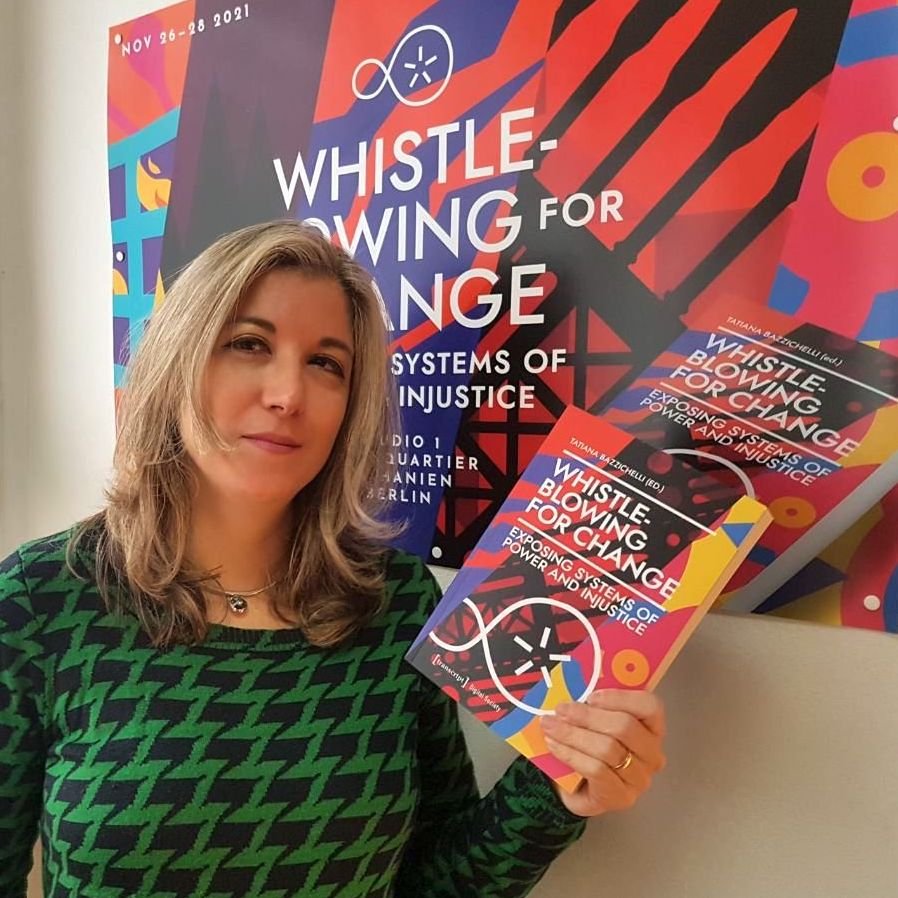

Suelette Dreyfus explores the personal and political dynamics behind national security whistleblowing, using the first meeting of WikiLeaks publisher Julian Assange and Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg in 2010 as a starting point. Drawing on a contemporary interview with Ellsberg, Dreyfus argues that what connects whistleblowers is a sense of imaginative empathy with the world outside institutions with compartmentalised security practices. The article makes the case for WikiLeaks to be considered as a journalistic organisation and describes Daniel Ellsberg’s efforts to force reform of the 1917 Espionage Act. The US indictment of Julian Assange in 2019-2020 is analysed as a significant escalation in the use of the Act. Finally, the essay draws parallels between whistleblowing revelations that assist in providing accountability for grave human rights violations and the treatment experienced by those making those revelations or bringing them to wider attention. Extradition as a vector of retaliation against whistleblowers, including those outside the national security realm, is also discussed.

-

Anna Myers explores a short 20-year history of whistleblowing law and practice, both in the UK and more widely via her own experiences working at a national non-profit legal advice centre dedicated to public interest whistleblowing. She describes the cultural, political, and economic context in which she encountered the (then) new law, the Public Interest Disclosure Act (1998) and what she learned about its legal and practical implications. Myers connects the protection of whistleblowers to the concept of public accountability and describes the inherent tension this creates in an era of de-regulation and globalising business growth. She focuses on two disasters caused by global oil giant BP, and how the Bank of Wachovia and the regulators responded to a whistleblower. In so doing, Myers challenges the reader to consider their wider collective responsibility. If we believe that whistleblowers are increasingly essential to holding power to account, what are we doing to help them make a difference?

-

As the former US Director of Reporters Without Borders working to advocate for press freedom worldwide, Delphine Halgand-Mishra was affected by how whistleblowers were being retaliated against in ways the journalists they worked with were not. This experience led her to her current role as the Executive Director of The Signals Network, which enables whistleblowers and international media investigations to work together to hold powerful interests accountable. In this chapter, she touches on the cultural perceptions of whistleblowers, the crucial role whistleblowers play in all our lives—exposing health hazards, market abuses, and privacy concerns, amongst others—and the difficult decisions whistleblowers face in what, for many, becomes a life-defining journey.

-

The easiest part of being a whistleblower is blowing the whistle. The most difficult part of being a whistleblower is ensuring that the results are worthwhile. Those who support the practice of whistleblowing can do little or nothing to help with the initial act of making public that which was intended to be secret. But there is a great deal they can do to assist with that which comes afterwards—and on which everything ultimately depends. A decade after the current wave of highly public whistleblowing kicked off in earnest, in tandem with the rise of WikiLeaks, we have enough information to start systematizing this, just as the adversary has systematized its own response. The essence of whistleblowing is narrative. There is no use simply releasing data if it is not publicized and placed in its proper context. This is understood on some level by those parties who wish to suppress, ignore, and otherwise divorce information from its proper context—and who in many cases are specially trained and equipped with this end in mind. This is unlike most parties on our own side, who must generally rely upon other advantages to achieve success in the information war that follows every act of whistleblowing.

-

Building networks of trust is an essential resource for whistleblowers. The social structure of friends, advocates, supporters and colleagues is extremely crucial before and after blowing the whistle. These open conclusions discuss how to make sensitive subjects and networks accessible to a larger public, giving insight on how to generate a dialogue among whistleblowers, artists, hackers, researchers, advocates and investigative journalists.

The practice of building networks of trust is linked to the activity of the Disruption Network Lab—such as the inter-disciplinary conferences bridging technology, politics and society, as well as local meetups hosted throughout the year. The common goal of this analysis is to connect different expertise, foster new investigations, and examine collective methods to expose systems of power and injustice.

-

The afterword aims to contextualize the different perspectives of truth telling that this book assembles in a societal analysis. It raises the question of where we stand on truth telling on three levels: the meta level of politics and democracy, the meso level of organizations and associations, and the micro level of the individual. At the level of politics, the practice of speaking truth to power goes to the heart of democracies, challenging us to accept that democratic structures are not built to last unchangeably, but that they are to be re-thought and re-built as soon as they take shape. Secondly, to normalize whistleblowing on the level of association means for our society, that we will need to establish the balancing act to stay true to social loyalties, as they are crucial for our social survival, but have a higher rule of morality and the rule of law, of democratically shared principles that prevail over any type of collective pressure or bond. Finally, the last question this afterward raises is, what it would mean for us as individuals to consider the possibility to step into the role of a whistleblower when the situation calls for it.

Contents · Back to top

Table of Contents

Introduction:

Tatiana Bazzichelli · Whistleblowing for Change: Disruption from Within

1. Whistleblowing: The Impact of Speaking Out

Billie Jean Winner-Davis · The Case of Reality L. Winner: A Mother’s View

John Kiriakou · National Security Whistleblowing: Torture and its Aftermath

Brandon Bryant · The Art of War, the Moral Law and the Art of Whistleblowing

Annie Machon · The Regulators of Last Resort

2. Art as Evidence: When Art Meets Whistleblowing

Tatiana Bazzichelli · Introducing Art as Evidence: The Artistic Response to Whistleblowing

Laura Poitras · The Art of Disclosure (Interview)

Trevor Paglen · Turnkey Tyranny, Surveillance and the Terror State / Charting the Invisible (Interview)

Robert Trafford · Socialised Evidence Production in a Post-Open Source World

3. Network Exposed: Tracking Systems of Control

Lisa Ling & Cian Westmoreland · The Kill Cloud: Real World Implications of Network Centric Warfare

Lauri Love · Sousveillance: Revolutionary Reappropriation of Vigilance by the Networked Polity

Joana Moll · Behind and Beyond: Tracking Narratives and Users’ Awareness

Denis “Jaromil” Roio · Hacker Ethics in 2021 (Interview)

4. Uncovering Corruption: Confronting Hidden Money & Power

Frederik Obermaier & Bastian Obermayer · How the Rich and the Powerful Hide Their Money (Interview)

Pelin Ünker · The Paradise Papers Effect in Turkey: No Resignation, No Prosecution, but Punishment for Journalism

Simona Levi · Improving Democracy through Digital Whistleblowing · Open-Source Device for Jailing Politicians

Christoph Trautvetter · Who Owns Our Cities? Exposing Dirty Money and Undemocratic Wealth in Berlin Real Estate

5. Exposing Injustice: Challenging Discrimination & Dominant Narratives

Daryl Davis · Another Type of Whistleblower: Exposing the Public to Overt & Covert Societal Truths

Charlotte Webb · Frosted Webs, Feminist Practice

Magnus Ag · In Our Data-driven Worlds Authoritarian States Know: Art Is the Lie That Tells the Truth

Os Keyes · Justice, Change and Technology: On the Limits of Whistleblowing

6. Silenced by Power: Repression, Isolation & Persecution

Daniel Hale · I Believe That It Is Wrong to Kill

Suelette Dreyfus with Naomi Colvin · Difficult Acts of Courage

Anna Myers · All I Ever Wanted to Know About Whistleblowing

Delphine Halgand-Mishra · How to Support Whistleblowers? The Signals Network Experience

Barrett Brown · The War Forward

Conclusion:

Tatiana Bazzichelli & Lieke Ploeger · Building Networks of Trust

Afterword:

Theresa Züger · The World We Think Is the World We Get

Contributors · Back to top

Contributors

Magnus Ag

Tatiana Bazzichelli

Barrett Brown

Brandon Bryant

Naomi Colvin

Daryl Davis

Suelette Dreyfus

Daniel Hale

Delphine Halgand

Os Keyes

John Kiriakou

Simona Levi

Lisa Ling

Lauri Love

Annie Machon

Joana Moll

Anna Myers

Frederik Obermaier

Bastian Obermayer

Trevor Paglen

Laura Poitras

Lieke Ploeger

Denis “Jaromil” Roio

Robert Trafford

Christoph Trautvetter

Pelin Ünker

Charlotte Webb

Cian Westmoreland

Billie Winner-Davis

Theresa Züger

Funding · Back to top

The book is funded by The Reva and David Logan Foundation (grant provided by NEO Philanthropy) and the Rudolf Augstein Foundation. Supported [in part] by a grant from the Open Society Initiative for Europe within the Open Society Foundations. Part of Re-Imagine Europe co-funded by the Creative Europe Programme of the European Union.