This is a chapter from Whistleblowing for Change: Exposing Systems of Power & Injustice - available in print, and free download. Read more about Art as Evidence

Help us organize more critical events & research by becoming a member.

The Art of Disclosure (2013-2021)

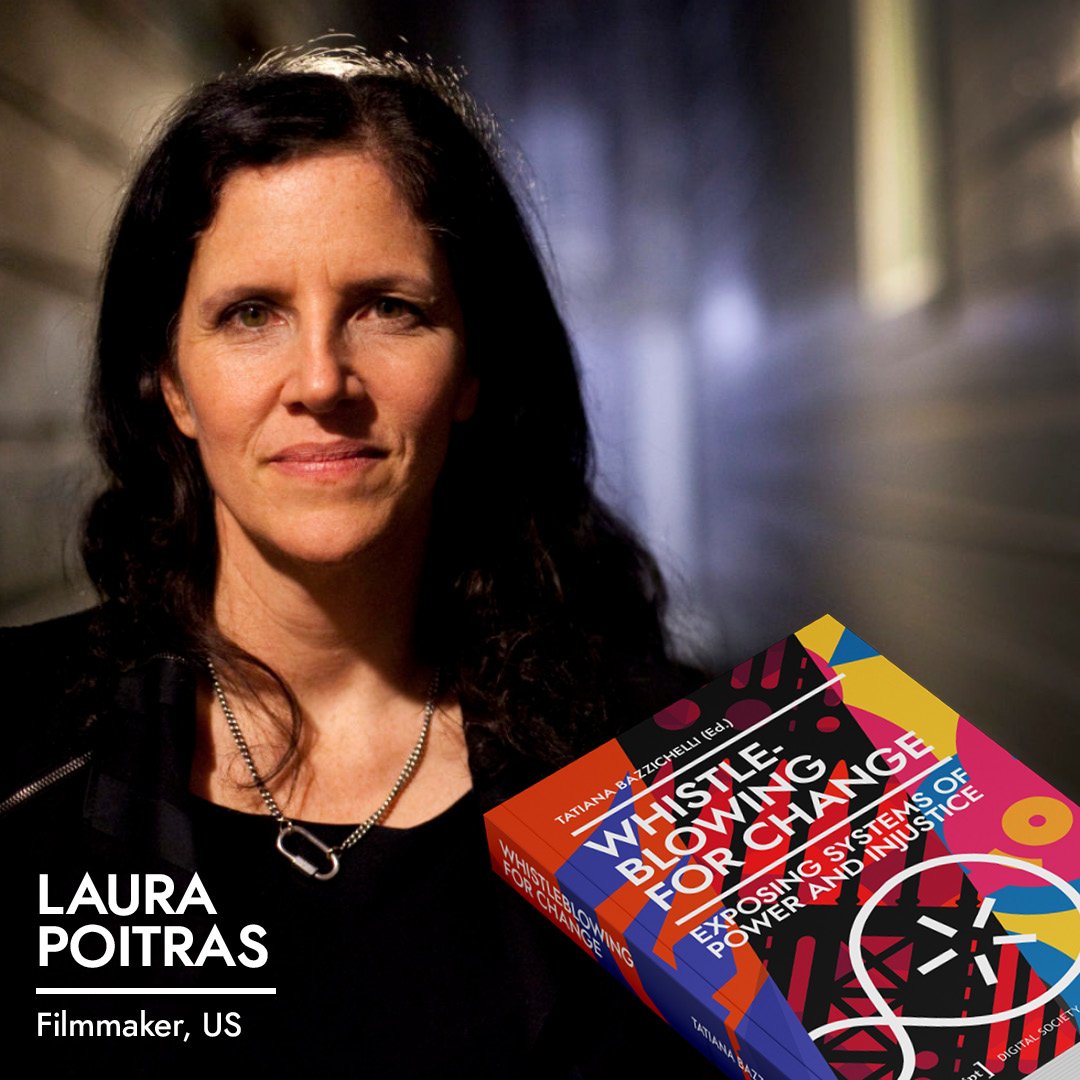

Two interviews with Laura Poitras by Tatiana Bazzichelli

The first interview with Laura Poitras was conducted in person in Berlin on November 28, 2013, and by email, in the context of our preparation for Laura Poitras’ keynote, “Art as Evidence”, at the transmediale festival edition “Afterglow”, which took place at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin from January 29 to February 2, 2014.

Laura Poitras is a filmmaker, journalist, and artist. Citizenfour, the third instalment of her post-9/11 Trilogy, won an Academy Award for Best Documentary, along with awards from the British Film Academy, Independent Spirit Awards, Director’s Guild of America, and the German Filmpreis. Part one of the trilogy, Academy Award-nominated My Country, My Country, about the US occupation of Iraq, premiered at the Berlinale. Part two, The Oath, on Guantanamo Bay Prison and the war on terror, also screened at the Berlinale and was nominated for two Emmy awards. Poitras’ reporting on NSA mass surveillance received a Pulitzer Prize for Public Service, along with many other journalism awards. Poitras was placed on US government secret watchlist in 2006. In 2015, she filed a successful lawsuit to obtain her classified FBI files.

The keynote opened the conference stream “Hashes to Ashes” on January 30. The aim of the conference stream was to highlight the pervasive process of silencing—and metaphorically reducing to ashes—activities that exposed misconducts in political, technological and economic systems, as well as to reflect on what burned underneath such processes, and to advocate for a different scenario. A shorter version of this interview was published on the transmediale magazine in January 2014.

The second interview was conducted in person in Berlin on June 16, 2021, for the book Whistleblowing for Change.

Tatiana Bazzichelli: By working on your documentaries about America post-9/11 and as a journalist exposing the NSA’s surveillance programs you have taken many risks, especially reporting on the lives of other people at risk. How do you deal with being both a subject and an observer in your work?

Laura Poitras: How I navigate being both an observer and a participant is different with each film. In the first film I made in Iraq, My Country, My Country, when I started working on post-9/11 issues, I am not in the film. That was a conscious decision because I didn’t want it to be a film about a reporter in a dangerous place. I wanted the sympathy to be for the Iraqis. It was a very deliberate rejection of mainstream coverage of the war. If people come away from the film and say: “Wow, this is what Iraqis are going through, and this family is really similar to my family,” then I succeeded. But how I handle my position has changed over time. In 2006, after I released my film about the occupation of Iraq, I became a target of the US government, placed on a terrorist watchlist, and started being detained at the US border, so I have been pushed into the story more and more.

With The Oath, the question was different. In that case I was editing with Jonathan Oppenheim, and we put together a rough cut of the film where I was not in it. We were doing test screenings and we realized that there was something that the viewers were really disturbed by—they were questioning the access. Rather than drawing them into the film, it was distracting them. Jonathan realized that we had to introduce me in the narrative and acknowledge the camera. There is a wonderful scene in the taxicab with Abu Jandal driving, and at one point his passenger asks: “What’s the camera for?” Abu Jandal gives this fantastic lie. This scene acknowledges the presence of the camera, the filmmaker, and we also learn that he is a really good liar.

Now I am working on a documentary about NSA surveillance and the Edward Snowden disclosures, and I will acknowledge my presence in the story because I have many different roles: I am the filmmaker; I am the person who Snowden contacted to share his disclosures, along with Glenn Greenwald; I am documenting the process of the reporting; and I am reporting on the disclosures. There is no way I can pretend I am not part of the story.

In terms of risk, the people I have filmed put their lives on the line. That was the case in Iraq, Yemen, and certainly now with Snowden’s disclosures. Snowden, William Binney, Thomas Drake, Jacob Appelbaum, Julian Assange, Sarah Harrison, and Glenn. Each of them is taking huge risks to expose the scope of NSA’s global surveillance. There are definitely risks I take in making these films, but they are lesser risks than the people that I have documented take.

TB: The previous films you directed tell us that history is a puzzle of events, and it is impossible to combine them without accessing pieces hidden by powerful forces. Do you think your films reached the objectives you wanted to communicate?

LP: Doing this work on America post-9/11, I’m interested in documenting how America exerts power in the world. I’m against the documentary tradition of just going to the “third world” and filming people suffering outside of context. I don’t want the audience to think that it’s some other reality that they have no connection with. I want to emotionally implicate the audience – especially US audiences—in the events they are seeing.

In terms of if my films reach their “objectives”, I think people assume because I make films with political content that I’m interested in political messages. That they are a means to an end, or a form of activism. But the success or failure of the films has to do with whether they succeed as films. Are they truthful? Do they take the audience on a journey, do they inform, do they challenge, and connect emotionally? Etc. I make films to discover things and challenge myself, and the audience.

Of course I want my work to have impact and reach wide audiences. To do that, I think they must work as art and as cinema. I made a film about the occupation of Iraq, but it didn’t end the Iraq war. Does that make it a failure? The NSA surveillance film will have more impact than my previous films, because of the magnitude of Snowden’s disclosures, but those disclosures are somewhat outside the documentary. Documentaries don’t exist to break news; they need to provide more lasting qualities to stand up over time. The issues in the film are about government surveillance and abuses of power, the loss of privacy and threat to the free Internet in the twenty-first century, etc., but the core of the film is about what happens when a few people take enormous risks to expose power and wrongdoing.

TB: Your films cannot be compared with news because news is always somehow distant, instead you get to know the people you are speaking about well, and you really see their point of view. It’s about their life, that they decide to share with you, so your role is different, and so are the roles of the people you’re filming.

LP: It’s different, for better or for worse. Documentaries take longer to complete, and some things need to be public immediately. You don’t want to hold back reporting on something like the Abu Ghraib photos. At the moment I am in a push/pull situation of reporting on the NSA documents and also editing the documentary. Whatever outcome there will be from these disclosures, the documentary will record that people took risks to disclose and report what the NSA is doing.

TB: What can we do as people working in the arts to help such a process of information disclosure, contributing to rewriting pieces of collective culture?

LP: I think of someone like Trevor Paglen, because he works on so many different levels. He works on an aesthetic level, and his secret geographies are also pieces of evidence that he’s trying to uncover. He combines them in this really beautiful way where you get both documentary evidence of places that we’re not supposed to see, and really spectacular images. I love that dialectical tension.

No artist, writer, or reporter works in a political vacuum; you’re always working in a political context, even if the subject of your work is not political issues. I guess I would say what I find the least interesting is art that references political realities, but there’s no real risk taking on the part of the art making, either on the structural form, or in the content of the work. It’s more like appropriation, where politics becomes appropriated by the art world’s trends. Any piece of work needs to work on its own terms, that’s the most important relevance it has, rather than any political relevance, and I think that that can be as profound or meaningful, like something that’s incredibly minimalist, that makes the viewer think in a different kind of way, and ignites your imagination. This is also a very political thing to do, although it’s not about war or politics.

TB: I am thinking about O' Say Can You See, your short movie about the Twin Towers and Ground Zero. There have been a lot of films about that, but I found it so interesting that you were not filming Ground Zero, but the people looking at it. For me that’s a clear artistic perspective.

LP: My education is in art and I have a social theory background—both inform my work. Every time you take on an issue or topic that you want to represent, it presents certain challenges and possibilities. At Ground Zero, people were looking at something that was gone and difficult to comprehend, but the emotions were so profound that we could represent what had happened in the absence of showing. There are limits to representation. Imagining what people were seeing was more powerful than showing it.

TB: Why did you start working on your trilogy about America post-9/11? How did such topics change your way of seeing society and politics?

LP: I was in New York on 9/11, and the days after you really felt that the world could go in so many different directions. In the aftermath of 9/11, and particularly in the build-up to the Iraq war, I felt that I had skills that can be used to understand and document what was happening. The US press totally failed the public after 9/11, becoming cheerleaders for the Iraq war. So I decided to go to Iraq and document the occupation on the ground. What are the human consequences of what the US is doing, and not just for Iraqis but also for the military that were asked to undertake this really flawed and horrific policy?

When I started that film, I didn’t think I was making a series of films about America post-9/11. I was naive and thought the US would at least pretend to respect the rule of law. Of course, America is built on a history of violence pre-9/11, but legalizing torture was something I never thought would happen in my lifetime. Justifying torture in legal memos, or creating the Guantanamo Bay Prison where people are held indefinitely without charge, that is a new chapter.

As a US citizen, these policies are done in my name. I have a certain platform and protection as a US citizen that allows me to address and expose these issues with less risk than others. Glenn and I have talked about this—about the obligation we have to investigate these policies because we are US citizens.

TB: Were you imagining this kind of parable would be touching people in their daily lives, like what’s happening with ethical resisters and whistleblowers?

LP: I never imagined there would be this kind of attacks on whistleblowers and journalists. Look at the resources the US has used in the post-9/11 era—and for what? More people now hate us. I have seen that first-hand. It’s baffling how the priorities have been calculated. I was placed on a government terrorist watchlist for making a documentary about the occupation of Iraq. That is an attack on the press.

I think we are in a new era where in the name of national security everything can be transgressed. The United States is doing things that I think if you had imagined it thirteen years ago you would be shocked. Like drone assassinations. How did we become a country that assassinates people based on SIM cards and phone numbers? Is that what you think of when you think of a democracy? Is that the world we want to live in?

TB: What is the last part of the trilogy teaching you, and how is this new experience adding meaning to the others described in the previous movies? What is coming next?

LP: The world that Snowden’s disclosures have opened is terrifying. I have worked in war zones, but doing this reporting is so much scarier. How this power operates and how it can strip citizens of the fundamental right to communicate and associate freely. The scope of the surveillance is so vast. It gets inside your head. It is violence.

About what’s next, I imagine that I will work on the issue of surveillance beyond the film. The scope of it goes beyond any one film.

TB: The fact that you are a woman dealing with sensitive subjects, traveling alone filming across off-limit countries, and developing technical skills to protect your data makes you very unique. How do you see such experiences from a woman/gender perspective?

LP: Speaking about technology, I do not think it is gender specific. I think that if you perceive the state as dangerous or a threat, which I do as a journalist who needs to protect sources, you have an obligation to learn how to use these tools to protect source material. Once you understand that a phone has a GPS device in it, you understand that it is geo-locating you and that potentially is dangerous, so you turn it off, or you stop carrying a phone. I do not think this is gender specific.

In terms of being a woman doing work in the field, overall it has made the work easier. In the Iraqi context, to be a woman allowed me more access because it is a very gender segregated society. If I was a man, I would have not been able to live in the same house as Dr. Riyadh and his family. I was able to film with the women and also film with men. Being a woman allowed me to have a certain kind of access that I would not have otherwise.

I also get access because often I work without a crew. When I was filming in Iraq, I remember I was inside the Green Zone and Richard Armitage gave the speech to the State Department. There wasn’t supposed to be any press there, but I just had a small camera and I started filming. He gave a speech where he said, “we are going change the face of the Middle East.” He was speaking to a group of people from the US State Department inside the Green Zone and he would have never said that if he thought that there was anyone from the press there.

TB: In my own writing I claim that networking is an artwork. The point is not to produce artistic objects, but to generate contexts of connectivity among people that are often unpredictable. Do you think that entering in connection with Snowden contributed to the production of an artwork in the form of ethical resistance?

LP: I feel that this film, or the experience of working on this film, has spilled outside of the filmmaking. In addition to making the film, many other things have emerged. Connections and relationships have been built. But all those kinds of things, and this network, happened because I was branching out of a more linear storytelling, because while I was working on the film, I was also doing a surveillance teach-in at Whitney with Jacob Appelbaum and William Binney, then a short film about Binney’s disclosures, and then when Snowden contacted me, that changed everything.

TB: Why do you think Snowden trusted you?

LP: I think he felt that if these disclosures are going to make an impact, that he wanted to reach out to people who were going to do it in a way that wasn’t going to be shut down by the US government. Ed had read that I was on a government watchlist and so he knew I understood the threat of surveillance. Glenn and I have both been outspoken on the topic of surveillance, US imperialism, and we had a track record of not being easily intimidated.

TB: I found it a really mature gesture that he decided to come out because he was afraid that other people could have been incriminated.

LP: When I received the email in which Ed told me I want you to put a target on my back, I was in shock for days. I thought my role as a journalist in this context was to protect his identity, and then he said, “What I’m asking you is not to protect my identity, but the opposite, to expose it.” And then he explained his reasons about how he didn’t want to cause harm to others, and that in the end it would lead back to him. He was incredibly brave. It still makes my heart skip a beat.

TB: I suppose you were also really shocked that Snowden is a really young guy.

LP: I was completely shocked when I met Snowden, and I saw how young he was. Glenn was too. We literally could not believe it—it took us a moment to adjust our expectations. I assumed he would be somebody much older, someone in the latter part of his career and life. I never imagined someone so young would risk so much. In retrospect, I understand it.

One of the most moving things that Snowden said when we were interviewing him in Hong Kong was that he remembers the internet before it was surveilled. He said that mankind has never created anything like it—a tool where people of all ages and cultures can communicate and engage in dialogue. It took someone with such love for the potential of the internet, to risk so much.

TB: You are part of transmediale 2014 with Jacob Appelbaum and Trevor Paglen in the keynote event ‘Art as Evidence’. How can art be evidence, and how do you put such a concept into practice via your work?

LP: What we’re doing in the talk is thinking about what tools and mediums we can use to translate evidence or information beyond simply revealing the facts, how people can experience that information differently, not just intellectually but emotionally or conceptually. Art allows so many ways to enter into a dialogue with an audience, and that’s a practice that I have done in my work, and that Trevor does with mapping secret geographies, and that Jake does with his photography focusing often on dissidents. We engage with the world in some kind of factual way, but we’re also translating information that we’re confronted with and sharing it with an audience. What we’re going to try to do at Art as Evidence is to explore those concepts and give examples of that.

We will combine each of our areas of interest and expertise. I think one of the topics we might discuss is space and surveillance. Trevor has been filming spy satellites. We have some other ideas. I don’t want to say too much.

On June 16, 2021, I met again Laura Poitras at Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (n.b.k.) gallery in Berlin, two days before the opening of her first European solo-show “Circles”. We decided to expand the previous interview, to reflect on the facts and experiences that have been taking place since the release of the documentary film Citizenfour in November 2014 to the present.

Tatiana Bazzichelli: After almost eight years from the time of our first interview many things changed. You and Glenn Greenwald left First Look Media, the organization that you co-founded in 2013. First Look’s publication, The Intercept, decided to shut down access to the Snowden Archive and dismissed the research team overseeing its security. Snowden is still in asylum in Moscow because of his act of whistleblowing. What does the closure of the Snowden Archive mean for the possibilities of further investigations of the material, and for holding the NSA accountable?

Laura Poitras: I was fired from First Look Media. I didn't just leave; I was terminated after speaking to the New York Times about The Intercept’s failure to protect whistleblower Reality Winner, and the lack of internal accountability and the cover-up that followed. This malpractice was a betrayal of the organization, which was founded by journalists to protect sources and whistleblowers and hold the powerful accountable. It is a scandal that an organization with such vast financial resources and digital security expertise made so many egregious mistakes, and then didn’t apply its own founding principles to itself.

The most shocking thing was that the Editor-in-Chief, Betsy Reed, took an active role in the investigation, which was investigating herself. This, and the many source-protection failures, were so scandalous that I felt a need to speak out about them.

If you allow a culture of impunity to persist, it endangers future sources and whistleblowers, so I spoke out, and I was fired a few weeks later. Glenn (Greenwald) resigned over many reasons, including the Reality Winner scandal.

What transpired in terms of the Snowden Archive was another devastating betrayal of the organization's founding principles. People put their lives on the line to reveal this information; Ed (Edward Snowden) put his life on the line, I put my life on the line, Glenn put his life on the line.

I am still shocked that The Intercept and Betsy Reed terminated the staff who oversaw the Snowden Archive’s security and destroyed the infrastructure built to provide secure access to the Archive for journalists at The Intercept and third-party journalists and international news organizations. This was not a budget decision. The Archive staff made up a miniscule 1.5% of The Intercept’s budget. It was a purging—the staff who were terminated were outspoken critics of leadership at The Intercept, especially their source protection failures.

The challenge with the Archive is how to scale the reporting, while also protecting the Archive from an unauthorized disclosure, leak, or theft. This requires systems of trust, technical expertise, and compartmentalization.

This is a very well-known security phrase: “privacy by design, not by trust.” That is what I mean by “compartmentalization” —essentially making it impossible for any one person to steal the archive, while also enabling many people to research it. The Intercept flushed it all down the toilet. I wrote to the Board of Directors to try and stop this from happening, but Betsy Reed and CEO Michael Bloom said the Snowden Archive was no longer of journalistic value to The Intercept.

I should stress that the Snowden Archive still exists, and there is still more to report. What The Intercept did was shut down its access and the secure infrastructure that enabled journalists at The Intercept and other newsrooms to access it.

This was a real betrayal of Ed and the many people who put so much effort into creating a secure infrastructure. If I were to reflect on my biggest regret in the NSA reporting knowing what I know now, it is joining The Intercept and First Look Media in 2014 instead of continuing to work with other news organizations.

TB: Is it possible to maintain secure regulated access to these kinds of leaks, years after the interest from news organizations has dissipated? What does the closure of the Snowden Archive tell us about how to deal with leaks in the future?

LP: I think we all learn from each other. There were certain things that we really did do right, and there were certain mistakes we made in these large leaks. I believe there will be future whistleblowers who will come forward, so I think we have to learn from the things that people did right and the things that people did wrong.

One of the brilliant things that Julian Assange and WikiLeaks did was to work with multiple international news organizations. It allows for the scaling of information and limits the possibility for the US government to put pressure on The Times or The Washington Post, for example, as it's harder if The Guardian and Der Spiegel and Le Monde are going ahead and publishing anyway. When you have a massive archive, this is a brilliant partnership model for working with multiple people, and is something we should absolutely carry forward. We also learned of the importance of using encryption from WikiLeaks, and that journalists cannot do their jobs if they don't understand how to protect their sources; they have a responsibility and duty of care.

If you look at the case of the unredacted leak of all the State Department cables, this wasn't the fault of WikiLeaks, it was the fault of their partners at The Guardian who didn't protect passwords. The unauthorized disclosure happened because a journalist published a password for an encrypted file.

In retrospect, if I were to get to redo 2014, I would have continued reporting with Der Spiegel and other news organizations. My former colleagues at The Intercept and First Look have said that all the important things in the Archive have been reported. That is not accurate. There is a vast amount of information that hasn't been reported of enormous contemporary and historical significance. The Snowden Archive contains a history of the Iraq war, the rise of the surveillance state, the global infrastructure of the US empire, etc.

TB: If you wanted to, could you access the archives and keep reporting?

LP: Yes. But no single person could ever fully report or grasp the scale of the information; it requires so many different skill sets, especially highly technical knowledge like crypto, etc.

TB: Your termination at The Intercept came two months after you spoke to the press about the Intercept’s failure to protect Reality Winner, and the lack of accountability that followed. You wrote that Winner was arrested before the story was even published, denying the crucial window of time for the focus to be on the information she revealed to the public. She is still detained at the moment, your contract at First Look was terminated, and very few people are following up on what she risked herself for. How can we guarantee an adequate protection for whistleblowers if they reach the press? How can we make possible that what she revealed still has an impact on society?

LP: That's part of the tragedy with Reality Winner: the FBI arrested her before the story was even published. She had no opportunity to seek legal advice, and she had no opportunity to see the impact of the story or communicate why she made the choices she did. She was also denied the ability to mount a defense because of all the evidence The Intercept provided the US government. This is because of the failures of The Intercept. They handed the document she leaked back to the government, they published metadata showing when and where the document was printed, and the reporter disclosed the city from which it was postmarked to a government contractor.

Imagine how different the outcome would have been in the case of Edward Snowden, had I gone to the US government and shared documents with them. Imagine how different the NSA story and Ed’s life would have been if he had been arrested and imprisoned before the stories were published? The public would never have heard his motivation, and it would have allowed the government to write its own narrative.

If the government had its way, I'd be in prison, and so would Ed. If I had made similar errors to those made at The Intercept, Ed would be in prison, and the public would not know his motivations. This crucial window of time changes outcomes.

The tragic thing about this is that The Intercept had so much money and digital security expertise, and they completely failed to protect Reality Winner. Furthermore, there was zero accountability for these failures: nobody was re-assigned or even lost a single day's pay. We are talking about people’s lives.

The Intercept was so lazy and reckless, and then they covered it up. To date, two people have been terminated after raising objections about The Intercept’s failure to protect Reality Winner: myself and the former head of research, Lynn Dombek.

TB: Would the model that was used for the Panama Papers work?

LP: I wasn't in the room or part of the reporting, though I did work on a film about the Panama Papers. From an outside perspective, it is the kind of model you need: one that brings a sense of scale to the information and also protects sources.

TB: The Espionage Act has been abused by the US government with many whistleblowers, including Reality Winner and Julian Assange. You worked on the film Risk (2017) that reported on the Assange Case. Julian Assange is risking extradition, although he is not a whistleblower but a publisher. The silence of the media about Assange is also a worrying signal in the framework of freedom of the press. Did you imagine these consequences of his work while making Risk?

LP: First of all, the indictment of Julian Assange under the Espionage Act is one of the gravest threats to press freedom that we've ever had, and a threat to First Amendment in the US. He's a publisher. He's not even a US citizen. And the fact that he's been indicted is absolutely terrifying. I wrote an op-ed in the New York Times in defense of Julian, saying that if he is guilty of violating the Espionage Act then so am I, arguing that it is used selectively against people who the government wants to silence and criminalize.

In terms of Julian’s situation, the US should absolutely drop the case. The judge in the UK denied the US government’s extradition request. The DoJ should drop the appeal. The charges go back a decade to 2010 and 2011. To put that into perspective, this case sets a precedent where the US government can go after any international journalist or publisher for things they published more than a decade ago.

When I was making Risk, I never had any doubt about the seriousness of the US government’s efforts to go after WikiLeaks. I’d also never imagined that Ecuador would withdraw his political asylum—it was clearly justified and based on documented facts. The right of asylum is something that's recognized internationally. If the subtext of the question is about the more critical aspects of Julian in the film, then I can address those too. There were scenes in the film Julian was unhappy with, where he's talking about the women who made the accusations. What is in the film are his own words. I didn't make the film because I was interested in those accusations, but I needed to address them in the film.

I have complete solidarity with Julian as a publisher. Julian has changed the landscape of journalism; the world is better for it and I defend it. But that doesn't mean that there's no room for criticism. He transformed journalism, exposed US war crimes and is absolutely being punished for it. This is a threat to every journalist in the world, and the lack of coverage is shocking.

TB: What happened to Julian Assange is a serious attempt in silencing the press, and setting a precedent that can be used against other journalists. It could apply to many others, including you. What are the risks for you, Glenn Greenwald and other journalists and news organizations who received and reported on the Snowden files and other leaks?

This is all about the selective use of Espionage Act. If you read the Espionage Act literally, the US government could choose to indict any national security journalist with exactly the same type of language that they're using to indict Julian. What's really staggering about Julian, however, is that he’s not even a US citizen. The Espionage Act has been abused consistently by Obama, Trump, and now Biden, to go after whistleblowers, journalists, and publishers. It should absolutely be abolished. This is why citizens and the press need to take a stand in defense of Julian Assange and press freedom.

TB: Coming back to the concept of Art as Evidence, the title of our keynote event at transmediale 2014, in the following year you worked on your first solo museum exhibition, Astro Noise, exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2016. The exhibition was a conceptual road map to understanding and navigating the landscape of total surveillance and the "war on terror." How did the exhibition contribute to producing evidence?

LP: Today we’re sitting at n.b.k. in Berlin showing new work which falls into that category. The collaboration that I'm doing with Sean Vegezzi is called Edgelands (2021—ongoing), and we've been documenting landscapes in New York using our skills as filmmakers and journalists to bring forth information to the public.

As a non-fiction filmmaker, I work with primary documents and documentary footage which in some cases can be evidence, such as the Snowden Archive. These primary materials then translate into ways in which you can communicate both what they reveal as information or evidence, and in terms of expressing larger issues, such as the dangers of surveillance. For instance, one of the pieces here is called ANARCHIST, which consists of images from the Snowden Archive and intercepts of signals communication that visualize the UK Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) and the US National Security Agency (NSA) hacking into Israeli drones that flew over the occupied territory of Gaza and the West Bank.

In one image, a drone is shown to be armed. So this is evidence hanging as a picture in a gallery space revealing armed drones which Israel has been consistently refusing to admit the existence of.

This is an example of art as evidence. The goal in my art is to make work that is truthful to the facts, but that also has emotional meaning. If you don't feel something, then I have failed. The primary material feeds into how to work with it, and how it can be expressed.

TB: Are you still of the same opinion today as in 2014 about art being functional in revealing truths and misconducts? You are currently collaborating with Forensic Architecture for the exhibition Investigative Commons at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin, and you are opening your new solo-show this Friday…

LP: I've worked with Forensic Architecture on two projects. I'm really excited about the work that they do. They use multiple disciplines and methodologies to understand ground truths and to present that in multiple contexts or forums. Their information is used in courtroom settings, because of the forensic nature of their work, and it’s also exhibited in museum spaces, providing counter-narratives to government narratives. We share an interest in ground truths, and making work using primary documents and deep dive analysis.

The Investigative Commons is a kind of laboratory. The idea is to bring together people who have similarities in methodologies, but also do different things, and to see how that might allow for generative conversations and new types of work. The collaboration I've done with them most recently is about the NSO Group, an Israeli cyber-weapons manufacturer, and their malware Pegasus, which has been used to target human rights defenders and journalists and is linked to the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi, because his close collaborator was targeted with Pegasus.

This is an investigation that Forensic Architecture undertook, and invited me to participate in. I participated in the interviewing of people who've been targeted by Pegasus. I made a film about Forensic Architecture’s process, and their investigation of the NSO as they map incidences of Pegasus infections to understand the connections between digital violence and physical violence. Forensic Architecture recently opened an office in Berlin and is partnering with the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), whose Founder, Wolfgang Kaleck, I’ve known for many years, and who was essential to my reporting around the Snowden work and who also represents Edward Snowden.

Regarding the n.b.k. exhibition, there are three main works: Edgelands, a collaboration with Sean Vegezzi, which is on three screens documenting locations in New York City that are linked by themes, including surveillance, state power, and incarceration, interconnected by the waterways of New York City. The collaboration with Forensic Architecture, also on three screens, includes my documentary about the investigation, on another screen is FA’s investigation into the corporate structure of NSO group, and finally a collaboration between Forensic Architecture and Brian Eno. In this project, Brian was asked to work with Forensic Architecture’s database of Pegasus infections and make a sonic representation of it.

The show is titled Circles; named after one of the subsidiaries of the NSO Group also called Circles, but it has other meanings about networks of collaborators and returning to Berlin.